This writer was born and raised in Nevada. Battle-born through and through. So it comes as quite a shock to hear that our namesake mountain range may be falling apart.

Funnily enough, the Sierra Nevada mountain range is, well, mostly in California. We got the good part, though, so it counts.

Sierra Nevada is a mountain range that runs 400 miles (640 km) along the American Cordillera. The American Cordilla is basically one giant mountain range going all the way from the arctic circle, down, down, down, into Antarctica. There are a couple countries in Central America that don’t have a range, and some of what would be mountains are under the Pacific Ocean, but when that ocean level drops, it’s there waiting.

In south America you might be familiar with it’s AKA, the Andes. Yup, still considered 1 chain. But enough about that, what’s going on with the western sierras?

Unfamiliar Information

Seismologist Deborah Kilb is a researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego. While she was analyzing California earthquake data over the last 4 decades, she found something peculiar. There have been recorded earthquakes underneath the Sierra Nevada mountains, at a depth that earthquakes shouldn’t be able to exist because of the heat and pressure.

“In Northern California usually the (earthquake) data goes down to about 10 kilometers (6 miles). In Southern California, they’ll go down a little bit deeper into 18 kilometers (11 miles),” said Kilb.

The problem is, the data she found shows the earthquakes being upwards of twice the depth. And they don’t seem to be stopping.

“The fact that we see some seismicity that’s below 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) — like 20 kilometers to 40 kilometers (25 miles) — is very odd,” Kilb said. “It’s not something you would typically see in crustal earthquakes.”

Kilb reached out to Vera Schulte-Pelkum, a research scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences and an associate research professor of geological sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder. Schulte-Pelkum had coincidentally already been studying the Sierra Nevadas, and their deep rock deformations.

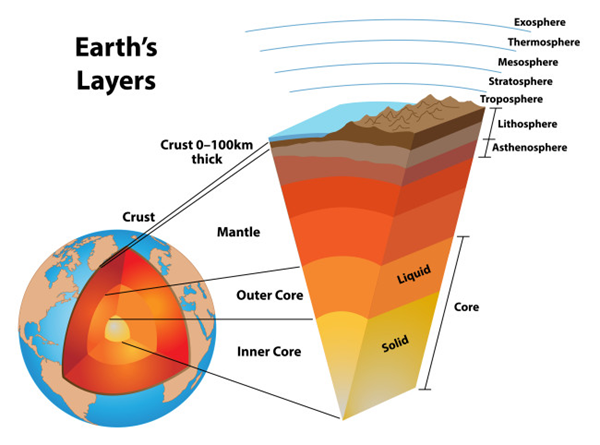

With this newly realized perspective, the two researchers conducted image analysis in the Sierra Nevadas using seismic waves to map Earth’s internal structure. They found that in the central region of the mountain range, the Earth’s crust is peeling away. This process is known as lithospheric foundering. I think I paid $75 for that at a spa last year, it wasn’t a pretty sight.

Connecting The Dots

The 2 researchers reported their findings to a geophysical research journal back in December.

The data was met with a strange realization- this had previously been imagined. A prior hypothesis was that the area had already seen peeling, when Earth’s outermost layer sinks into the lower layer of the mantle. But the theory had been that it was a past event. This data shows that it may be an ongoing process.

“We compared notes and realized that my strange rock fabric (the arrangement of rocks) signals and her strange deep earthquakes were in the same area,” Schulte-Pelkum said. “So then we decided to look at it more closely, and found this whole story.”

What these researchers have discovered may give a more detailed look into the exact process of continent formation. The finding could also help scientists identify more areas where this process is happening as well as provide a better understanding of earthquakes and how our planet operates, Schulte-Pelkum said.

Lithospheric Foundering

Earth’s outermost layer, the lithosphere, is made up of a rigid crust and the top part of the mantle. Which is in a denser, but more fluid state. This layer also contains Earth’s oceanic crust — a thinner and denser layer below the oceans . And the continental crust that sits above this layer. But how these sublayers manage to exist in this ideal state, with the continents on top, is something of a mystery, Schulte-Pelkum said.

“The continents just happened to be sticking up above the current sea level, luckily for us, because … they’re made of less dense minerals on average.” Schulte-Pelkum said. “To make it sit higher (in the first place), you have to get rid of some of the dense stuff.”

Lithospheric foundering is the process of the denser materials being pulled to the bottom. This makes the less dense material emerge at the top, resulting in land creation. “It’s dumping some of this denser stuff into this gooey, solid mantle layer underneath and sort of basically detaching it so it stops pulling on the less dense stuff above,” she explained.

Not Typical

Within the imaging below the Sierra Nevada, the researchers found a distinct layer within the mantle about 40 to 70 kilometers (25 to 43 miles) deep. This layer had specific imprints that gradually ascended, the data showed.

If one were to have a block of clay that had spots of different colored clay throughout. Then squeeze the clay between their hands, the spots would start to turn into stripes. This is similar to how the rock deformations appear, Schulte-Pelkum said.

In the southern Sierra, the dense rocks had the strongest inherent stripes. They were shown to have already pulled away from the crust. However, in the central region this process seems to be continuing. In the northern Sierra, there currently is no sign of alteration. This strange formation underneath the central Sierra would indicate why those deep earthquakes are occurring. Since the crust is abnormally thick from this foundering, and colder than the average mantle material typically that deep. Kilb’s findings seem to line up with the recipe for earthquake soup.

“Rock takes a really long time to warm up or cool down. So if you move some stuff, you know, by pulling it down or pushing it up, it takes a while for it to adjust its temperature,” Schulte-Pelkum said.

Fascinating Evidence

This foundering process isn’t exactly easily witnessed. It can’t be seen from the surface, and takes quite some time to achieve. The southern Sierra is believed to have gone through its foundering 3-4 million years ago.

These naturally occurring events do happen around the world from time to time, Schulte-Pelkum said. “Geologically speaking, this is a pretty quick process with long periods of stability in between. … This (lithosphere foundering) probably started happening a long time ago when we started building continents, and (the continents) have gotten bigger over time. So it’s just sort of this punctuated, localized thing,” she added.

Never-Ending Discussion

The Sierra Nevada range has been the subject of debate for many years among Geologists. This is due to the mantle’s makeup underneath the southern Nevadas. While the theory of lithospheric foundering is a prevalent understanding, other scientists have differing opinions. Subduction, when oceanic plates move underneath other less dense plates, cause landscape changes.

“There are really two competing hypotheses to explain all these data, and you don’t really get that very often in geology. … So this paper is going to add to that whole discussion in a really neat way,” said Mitchell McMillan, a research geologist and postdoctoral fellow at Georgia Tech.

Additional studies into the matter could help scientists form a deeper understanding of how the Earth evolves over time. If the lithospheric foundering continues under the Nevadas, the land could likely stretch vertically. It would drastically change how the landscape looks now, McMillan said. He did point out that this process could take over several hundred thousand years, up to a few million years. I’ll clear my calendar.

“It’s really fascinating to think about how you could be … hiking in the Sierra or in the foothills, or even anywhere else on a continent. And, you know, there’s stuff going on really deep underneath you that we’re not aware of,” Schulte-Pelkum said.

“We sort of owe our existence on land to these processes happening. If the Earth hadn’t made continents, then we’d be very different creatures. … We evolved because the planet evolved the way it did. So just sort of understanding the whole system that you’re part of, I think, has value — beyond just less monetary damage and less human impact during, say, an earthquake,” she added.

I think those that suffered in Myanmar last month, would welcome less damage and human loss. But that’s just me.